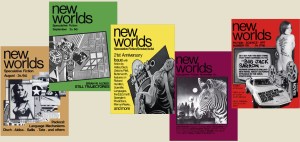

The other day Michael Moorcock was kind enough to post a link to this blog on his Facebook page and it brought a lot of new readers here, for which I’m grateful. Quite a few of them seem to be interested in the goings-on of long ago, especially those connected with New Worlds® and its various characters, which is as surprising to me as it’s welcome. I’ve touched on these matters in a few earlier posts and I plan to write more along those lines, but in the meantime here’s a bit more about the magazine itself and my involvement with it.

New Worlds was launched as a professional magazine in 1946, which makes it the same age as me, but I didn’t learn of its existence until 1967 when I was at university and a group of us undergraduate psychologists were treated to a talk on science fiction by some self-styled expert whose name I’ve forgotten, and one of the questions at the end came from a bearded fellow at the back who was indignant that the lecturer had said nothing about the new wave in sf that was beginning to cause a stir in magazines like New Worlds (he said). This upstart proved to be a newly-arrived graduate student called Bob Marsden whom I got to know a bit. He was engaged in a project on creativity and for some reason decided to interview me as part of his research, though I had shown scant evidence of creativity at the time: some student journalism and a few appalling poems and short stories. Bob says that I’d be highly embarrassed to hear that tape now, which I can well believe. The poems and stories are staying right where they are, buried in ancient files.

At the time I was keenly interested in decadent literature from Wilde via Huysmans to Jarry, fancying myself as something of an aesthete and trying my hand at drawing in the manner of Beardsley and a few others, and I recall telling Bob that I was rather fixated in the 1890s, but that was by no means the whole picture. In fact I read all sorts of extra-curricular stuff at university, including a lot of writing by Kerouac and the other beats, Max Beerbohm, the complete Fu Manchu novels by Sax Rohmer, Kafka, Flann O’Brien, Raymond Chandler, humorous pieces by Damon Runyon, S.J. Perelman and Dorothy Parker, and much much more. University shouldn’t just be about passing exams, boozing, and discovering that sex with a woman is actually possible, which for me at my Methodist boarding school it certainly hadn’t been.

I liked science fiction and imaginative writing generally (Poe, Haggard, Wells, Conan Doyle, Orwell, Huxley and Golding) but not much of the hard-core generic material had come my way. I’d read the books that were being published by Penguin — John Wyndham’s and the anthologies edited by Brian Aldiss, and a few other things — but not much else was available in Sheffield at the time. I bought a copy of Kingsley Amis’s New Maps of Hell and from it made a list of the sf novels that looked as though they might be worth reading (Blish, Kornbluth, Bester), and couldn’t find any of them. But I got a nice surprise when my friend James told me that as a pupil at King Edward’s School in Birmingham he’d been presented with a set of books by one of the school’s old boys as a reward for something or other but they hadn’t been to his taste — they seemed to be all about elves, he said disgustedly — but they might be to mine, with my eccentric tastes in literature. This turned out to be The Lord of the Rings, and I was instantly hooked. James saw me enjoying his books and decided that perhaps he should give them another chance, and soon he was hooked too.  We swapped the books to and fro until we both got to the same point in the story, then we went down to the pub to discuss it and drown our sorrows when Gandalf was killed by the balrog and speculate about whether Frodo would eventually make it to Mordor. I got hold of a copy of The Hobbit, which wasn’t easy to find at that time, and we devoured that too. In Sheffield there was no sign of New Worlds, however.

We swapped the books to and fro until we both got to the same point in the story, then we went down to the pub to discuss it and drown our sorrows when Gandalf was killed by the balrog and speculate about whether Frodo would eventually make it to Mordor. I got hold of a copy of The Hobbit, which wasn’t easy to find at that time, and we devoured that too. In Sheffield there was no sign of New Worlds, however.

It wasn’t until I moved to London in 1967 that I actually set eyes on a copy of it. Some university friends were paying me a visit in my new surroundings (a spacious flat in Belsize Park shared with James and a colleague of his called Willoughby) and they said that I ought to meet some friends of theirs who lived nearby. Mike and Di were living in a tiny, dismal bedsit in Tufnell Park, and we hit it off instantly. They had dropped out of college and come to London where Mike was trying to make it as a writer, while to help them survive Di had got a job with Exquisite Form Brassières in an office behind Oxford Street. The initial bond was Tolkien. I’d acquired my own set of LotR and had now read it for a second time, but Mike had read it FIVE TIMES and he’d had a short story published in a fantasy magazine while still at college, and a tight friendship developed in which Mike and Di took me under their wing and in the process gave me a crash course in modern science fiction, amongst other things. Their bookcase held not only the three volumes of Tolkein but volumes from the Phoenix edition of D.H Lawrence, Dune (which Mike had specially requested as his 21st-birthday present), various works by Samuel Beckett, well-thumbed paperbacks by Thomas Pynchon, Samuel R. Delany, Alfred Bester and Kurt Vonnegut Jr., and a couple of stout volumes bearing the name of E.E. ‘Doc’ Smith on the spines — and much more besides. They also had a portable record player and albums by Dylan, Hendrix, Mayall with Eric Clapton, The Velvet Underground and — a particular favourite of theirs — Roy Harper. This seemed like a very good place to hang out.

Mike and Di read New Worlds avidly, and had not only the latest issues but a collection of earlier issues from the period when it was a paperback book published by Compact rather than a magazine, and soon I was buying and reading New Worlds myself and looking out for back numbers wherever I could find them, and from them I learned that it had quite an illustrious history. It had been brought into being by a group of science fiction fans in post-war London who felt that there should be a British sf magazine to rival the American ones that dominated the market, and after sort of pre-existence as an amateur mag it found a publisher and was launched as what is termed a prozine under the editorship of John Carnell, who everyone called Ted. [Note by the way that aficionados refer to this genre as sf (pronounced ‘ess-eff’) and never as sci-fi.] By the time I arrived in London Carnell was regarded by the younger generation as a bit of an old fogey but that was unfair, for he was a dedicated and at times inspirational editor, opening New Worlds’s doors not only to British writers like John Wyndham and Arthur C. Clarke and a host of new local talent but welcoming US writers like Harry Harrison, Theodore Sturgeon, Robert Silverberg, Harlan Ellison, Philip K. Dick and Robert Sheckley into its pages, some of whom were having difficulty getting their more adventurous stories accepted in their own country. New Worlds did well enough to spawn a sister publication too, Science Fantasy, also edited by Carnell, which published some interesting work including ‘Deep Fix’ by a young Michael Moorcock and the first appearance of his soon-to-be-famous character Elric.

The outstanding writer in the science fiction world was J.G. Ballard, whose dazzling early stories had been published in New Worlds in the 1950s and early 1960s by Ted Carnell and when he published ‘The Terminal Beach’ in 1964 it caused a sensation among the younger readers and effectively ushered in the New Wave. Under Mike and Di’s tutelage I soon caught up with all this, and when Michael Moorcock took over the editorship later that year and championed Ballard New Worlds became the New Wave’s home, attracting a roster of young writers who enthusiastically embraced the opportunity to experiment with new forms and subject-matter. Through Mike and Di I got to know quite a few of them. Some of them called at the Tufnell Park bedsit while I was there just hanging out. If we occasionally scraped together the money for a bottle of wine it was just the one and it had to be shared between all of us. Usually there was no money for more than the basic necessities to stay alive, though Di was ok for bras, and she made Mike a warm waistcoat by stitching together free carpet samples [photo to be inserted when I find it].

One frequent caller was Graham Hall who offered to buy Di from Mike for £100, and they were so broke that they considered this very seriously before eventually turning it down. Graham was richer than the rest of us as apart from his involvement with New Worlds — he’d had three short stories published in its pages and was sometimes billed as Assistant Editor, which made him a big shot in this little world — he wrote scripts for D.C. Thomson’s comics, mostly schoolgirl yarns for Bunty. This enabled him to buy a spanking new Hillman Imp, a tiny car for a big guy, in which he drove up to the head office in Dundee from time to time. He offered to show some of my lighter work to Thomson’s to see if I might cut it as an artist for the Beano or Dandy, but he never did, and I realized that as far as I was concerned Graham was playing manipulative and rather cruel games. He was a troubled person — family issues that we never really found out about — and was rather theatrically saying that he meant to drink himself to death, so he became known to us as ‘Deathwish’ Hall. Whatever. He didn’t like me, and I soon grew to dislike him right back.

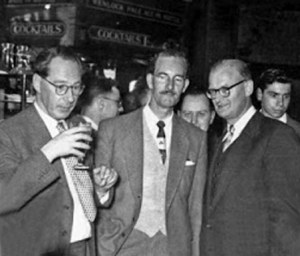

By way of diversion Mike and Di took me to meet the established sf writer John Brunner at his luxurious flat in Frognall where he too was extremely rude to me for no obvious reason and with no provocation, but the real meeting-place was The Globe pub in Hatton Garden where sf writers and fans gathered on the first Thursday of every month, and there things were much more congenial.

Here I met, or at least set eyes on, people like Brian Aldiss, Chris Priest, Ted Carnell, Arthur C. Clarke, Ted Tubb, Tom Disch (who tried to chat me up but not being gay I demurred), John Sladek (who later became a good friend), and many more whose names and faces have faded into the mists of time. One surprise was hearing a voice saying “Hello Richard, what the hell are you doing here?” It was Bob Marsden down in London from Sheffield, who turned out to have known Mike and Di for some time and who was already a member of their little coterie. I saw a lot of Bob after that and he too became a close friend. Most significantly for me at the time, though, it was at The Globe that I first came across Michael Moorcock and Charles Platt — and I mean no disrespect to Mr Moorcock if I refer to him by his surname in what follows, as there’s already one Mike in this story. The Mike I already knew was Mike Harrison, who wrote as M. John Harrison as there was already a fairly well-known writer called Michael Harrison.

Back in Tufnell Park, Mike was very keen to be part of the New Wave and to be published in New Worlds, and was writing rather Ballardian stories to start with and planning a sort of campaign to achieve it. He acquired an agent — an important step for any young writer — in the shape of Ted Carnell, now retired from his editorial duties, who got some of Mike’s stories published in places like Transatlantic Review and New Writings in SF for extremely modest fees, but New Worlds remained elusive until some personal contacts were made. It happened in a roundabout way. Bob had moved to London to pursue his study of creativity which involved interviewing some of the New Worlds writers, and Charles Platt had fixed him up with a flat right opposite the one he shared with Diane Lambert in Portobello Road and which served as the New Worlds office. Mike and Di and I sometimes went over to Bob’s on a Saturday evening, where it turned out that the flat below Bob’s was currently occupied by James Sallis, an American who had seemingly appeared from nowhere to become a co-editor of New Worlds, and who had a vintage Gibson guitar and an electric guitar too, plus a set of harmonicas on all of which he could play a pretty decent blues or two. We usually took our own guitars with us on such outings and before long we were jamming with James Sallis, and through him Mike got to know Moorcock and was soon appointed Literary Editor of New Worlds, the monthly fee for which enabled Mike and Di to move to a slightly larger flat (a sitting room containing twin beds with an adjoining kitchen) in Camden Town.

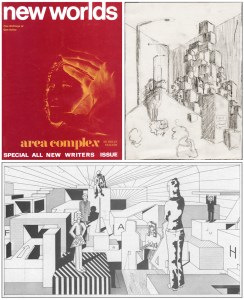

Bob was sharing his top-floor flat with a university friend of his called Marek Obtulowicz who was studying to be an architect, while the ground-floor flat was occupied by my non-pal Graham Hall, who was now editing a ‘New Writers’ issue of New Worlds in which Mike was to make his debut with his story ‘Baa Baa Blocksheep’. Mike wanted me to illustrate this and I was keen to do it and produced a very rough pencilled rough (the blobs in the foreground were going to be sheep) which was shown to Graham, but Graham had different ideas and gave to job to Marek. I liked Marek but this really pissed me off, and I had to watch helplessly as the New Writers issue (No. 184) appeared with Mike and other friends like Graham Charnock and R.G. Meadley in it, but not me. This may have been because Marek’s drawing was much better than mine, of course. Bob had a story published in New Worlds too and I didn’t get to illustrate that either.

My own first appearance in New Worlds was actually as a book reviewer (commissioned by Mike) in No. 187 in February 1969 and I was ridiculously proud to be appearing in a national magazine, buying extra copies to send to my family and friends who were polite but less impressed than I’d hoped they’d be, which I gather is often the way with these things. My parents thought that I was wasting my time on this stuff when I should have been concentrating on getting my Ph.D and perhaps becoming a junior lecturer in Psychology somewhere, a prospect that was becoming less appealing by the minute. My first illustrations appeared in No. 189 accompanying Mike Harrison’s first Jerry Cornelius story ‘The Ash Circus’ — Mike had liked my drawings and recommended me — which for some bizarre and forgotten reason I’d done in charcoal: a medium I’d never used before and never would again.

[I should probably take a break here to explain the Jerry Cornelius phenomenon which played a large part in our lives at this time, but that would mean introducing other characters like the artist Mal Dean and the publishers [Clive] Allison & [Margaret] Busby, other publications like International Times and Frendz, Jon Finch who played Jerry in the film of The Final Programme, and all the other authors who wrote Jerry Cornelius stories … Another time maybe.]

Reverting to pen and ink more of my illustrations followed in the next few issues [I’ve scanned some of them for my Gallery here for anyone who’s interested], and by No. 195 I was on the staff and credited as Designer — I’ve already written about how I became a New Worlds staffer here — though to be honest at the start I was merely assisting Charles with the designs and layouts. I was quickly learning the mysteries of Letraset, Cow Gum and Process White, however, and Charles was kind to me and generous in letting me try my own design wings occasionally, while his partner Diane Lambert fed me with home-made apple crumble.

With the ice broken Mike and Di and I took to spending Saturday evenings at Moorcock’s large flat in Ladbroke Grove. By now I’d learned to drive and got a second-hand car thanks to my mum’s generosity so getting there was no problem, and we no longer had to race to get the last tube home from wherever we were. When we arrived at the flat in the early evening there were usually other people around, including the Moorcocks’ beautiful kids Sophie and Katie who were soon packed off to bed; Jim Cawthorn was often there too, Moorcock’s long-standing friend and a talented illustrator who was friendly and complimentary about my drawings when I could make out what he was saying in his thick Geordie accent; Lang Jones sometimes popped by with proofs that he was collecting or returning; Keith Roberts was sometimes a large gloomy presence by the fireside; John Clute was in the process of becoming the magazine’s lead reviewer and was frequently closeted in the top bedroom with Moorcock discussing critical matters…

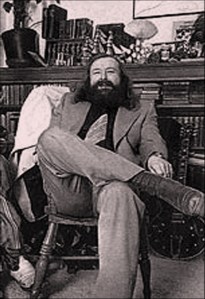

Others came and went and exchanged a bit of friendly chat — I never once saw all the New Worlds staff in the same place at the same time, and a couple of them like Christopher Finch and Eduardo Paolozzi (‘Aeronautics Adviser’) I never met at all — but as the evening wore on they all melted away leaving just the two Mikes, Di and me in the large sitting-room with pictures by Cawthorn, Peake and Paolozzi on the walls and bookshelves on either side of the ornate marble fireplace stuffed with first editions of Mervyn Peake and T.H. White, with the Nebula award that Moorcock had won for Behold the Man (first published in New Worlds) on the mantelpiece. Moorcock usually sat in the upright wooden chair beside the small desk where he wrote, Mike sat in a smaller chair opposite him, while Di and I spread ourselves out on the huge lime-green sofa that straddled the room — and we talked, talked and talked, often very late into the night.

As we arrived there was usually some banter about the difficulties we’d had getting there, whether dodging the machine-gun fire of insurrectionists or escaping an alien invasion, and how we’d only made it to Ladbroke Grove by the skin of our teeth, then we settled down to the business of the night. This was the first time I’d got to have a good look at Moorcock and come to know him, who was (and remains) a big guy, about 6ft 2in and by no means slimmest person in the world, but a charismatic figure and a very amusing talker. The other Mike was not tall but he was wiry and infectiously enthusiastic, while Di was calmer and of medium size with long straight blonde hair. We all had long hair at the time, in fact, though mine would only grow long enough for me to suck the ends of it, to my chagrin. We all smoked cigarettes continually, but otherwise these sessions were remarkably austere with no food or booze, no hard drugs — not yet anyway — and the only refreshment was occasional cups of tea brought by Mike’s wife Hilary from the kitchen downstairs. I was interested to find that the Moorcocks had a cat named Bilbo and a dog named Precious.

The first business of the evening was usually to scan the trade papers to see what forthcoming books we might want to review — Mike was the Literary Editor, remember, and responsible for distributing the books to reviewers and sometimes nursemaiding them through the reviewing process — whilst I would unveil any new drawings or designs I’d done to see what the others thought of them. After that we sometimes played our guitars for a while or listened to any new records we’d got; Moorcock was into Creedence Clearwater Revival at the time (“good, tight band”) but Mike’s attempts to get him to like Roy Harper fell on deaf ears. Then we talked.

The conversation was often hilarious and impossible to evoke here — as the saying goes, you had to be there — but there were visual diversions too, as when Moorcock sometimes appeared clad only in an enormous nightgown or when he would disappear for a while and return with his beard dripping with blood: when peckish he liked to get a slab of raw liver from the kitchen and swallow it whole (“Slides down a treat’), to our mingled amusement and disgust. When someone, usually the prolific Moorcock, had a new book coming out or had given an interview to a newspaper or magazine we’d pile into my car and go down to Fleet Street to pick up the early editions, which went on sale there soon after midnight. It was an exciting time. The Beatles were still around and had just set up their Apple HQ in Saville Row which was advertising in the underground press for creative talent of various kinds which they said they might support, so Moorcock and Beatle-friend Bill Harry paid Apple a visit to see if they could score some Beatles money for New Worlds. They managed to have a chat with Derek Taylor and a few words with George Harrison but there were rumours that Apple was in trouble and they decided that any spare money should go into Apple Records rather than avante-garde sf mags. It was also exciting for me to see a succession of books being published from people I now knew personally, some of whom I could regard as friends: the two Mikes and Charles, obviously, but also Lang Jones, Tom Disch, John Sladek, Harry Harrison, Brian Aldiss, Chris Priest, Keith Roberts, and some I knew only very casually. I was often given free copies by the writers I knew best.

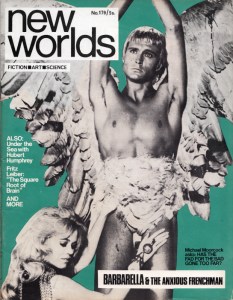

There were signs that science fiction was actually becoming fashionable. Earlier it had often seemed, especially to outsiders, as a minority taste fit only for lab assistants and nerds — a calumny on the percipient people who had discerned its merits all along — but when David Bowie recorded ‘Space Oddity’ things changed, with many others recording songs suffused with imagery from sf and fantasy, though some of the bands went more for the costumes than the content. But in 1972 alone there was T.Rex’s ‘Metal Guru’, Elton John’s ‘Rocket Man’, Bowie’s ‘Starman’, Hawkwind’s ‘Silver Machine’ and Billy Preston’s ‘Outa-Space’, while John Lennon’s ‘Across the Universe’ (on a charity album that Charles had) was still played frequently in the office. There were sf movies too, notably 2001: a Space Odyssey based on a story that had appeared in Carnell’s New Worlds, which signalled the end of the crude movies that had hitherto presented sf to the masses. This vogue didn’t immediately translate into increased sales of sf books and magazines, however, and it certainly didn’t for New Worlds which preferred to set trends rather than follow them and was in any case having problems with distribution. (Brian Aldiss once wrote that he had paid New Worlds a visit and found Charles and Diane selling copies on a street corner outside in the snow.) The nearest the magazine ever got to a movie tie-in was with Barbarella, with a cover collage by Charles which included a stll from the film but inside was a highly dismissive piece entitled ‘Barbarella and the Anxious Frenchmen’.

Graham Hall disappeared to university as a mature student (Hooray!) and Jim Sallis had returned to the USA for reasons of his own after publishing a critical piece called Orthographies whose purport baffled even the keenest minds among us, so the two Mikes and Di and I became what has been called the New Worlds inner circle, and at one stage Moorcock even suggested that we form ourselves into a company with the four of us as directors. That didn’t happen, but we plotted and schemed, exchanged gossip about writers and publishers and agents, endlessly discussed the writers and publishers and agents we liked and didn’t like, got excited about some of the new writers who were appearing, sneered at some of the older ones who we felt weren’t moving with the times (John Brunner was one), and made our plans for novels, short stories, anthologies, cartoon strips …

Over in Portobello Road I continued to work on the design and layouts of the magazine, unaware that things were starting to fall apart there. For me, it was an amusing place to work and hang out. Charles had a large tape recorder which played music almost continuously and sometimes as I arrived I’d hear Bob Dylan singing “Something is happening here but you don’t know what it is, do you Mr Jones?” which may have been coincidental — or was it?

I never knew what to expect. The large notice-board which covered one wall was suddenly filled with pages from the Beano, mostly spreads of Dennis the Menace with his dog Gnasher (Mike and Di got a black cat which they called Gnasher) and a character that Charles evidently liked called Corporal Clott. There were boxes of pin-up photos of girls in various states of undress classified in different ways for one of Charles’s other activities compiling girlie mags. On one occasion I found Scalextric tracks snaking all around the flat, and in those days before affordable answering machines Charles had made his own from Meccano ingeniously linked to the tape recorder, which was clunky but worked: a foretaste of many devices that Charles would make in the ensuing years and include in his very successful Make books.

Another time I knocked on the door of the Portobello Road office and as usual Diane opened an upstairs window and threw down the keys to let me in, then I went upstairs to find Charles wrestling with a problem. “Ah Richard,” he said, “Perhaps you can help with this.”

“I’ll certainly try,” I said.

“If a couple jumped out of a burning plane without parachutes” he said without preamble “would they be able to couple and reach a climax before they hit the ground?”

“Just hit the ground splat?” I ventured.

“Splat indeed,” said Charles.

It seemed that Charles was writing an erotic novel for Essex House, a Los Angeles publisher who was commissioning such work from some quite well-known writers like Philip José Farmer, David Meltzer and Charles Bukowski, and from a few other things that Charles said I gathered that this one would take the form of a sort of Quest for the Ultimate Orgasm, with many bizarre variations on the basic theme.

Of course I had no idea if the situation Charles envisaged was possible and began thinking about how these two might get (their) things together in freefall — no easy matter, I felt, before they could even start with the jiggy-jiggy stuff — but Charles was more concerned with the physics of the situation, scribbling calculations involving height, weight, altitude, terminal velocity, wind speed etc. Science fiction of that sort had to be plausible.

Essex House didn’t last long and I don’t know whether Charles’s erotic novel ever saw publication, though he did publish one called The Gas which became somewhat notorious. Back in the real world two doors along, John Sladek and his new girlfriend were enthusiastically exploring these things in a more practical way, including a technique they’d devised involving a hostess trolley … but I digress.

I didn’t know that Charles’s relationship with Diane was in difficulties and that he was feeling distinctly burnt-out having been producing New Worlds on a monthly schedule for several years by now, and recently I apologized for not being more understanding.

Charles replied: ‘”Burnt out” is a mild term for the state that Moorcock and I were in by the beginning of 1970. […] Kind of you to imagine that you could have helped, but — no, not possible, there was nothing anyone could do to help! Running away was the only remaining option, and not only for me.’ Charles has published his own account [here] of this period which anyone interested in this stuff should read. Moorcock too has been publishing his own (fictionalized) memories of these events, the second volume to be published soon with the first one already available here: further essential reading for New Worlds fans.

Our Saturday night sessions chez Moorcock continued for some time yet, however, and it became clear that the two Mikes were engaged in a sort of bonding process, talking about their own works-in-progress and putting the sf world to rights, which often involved scathing attacks on the sort of writers they particularly disliked. I recall one long night when the victim was Larry Niven who to them represented almost everything that was wrong with sf (which by the way was now being taken to stand for ‘speculative fiction’ rather than ‘science fiction’), but never having read a word of Niven and knowing nothing about him personally I had nothing to contribute to the discussion and was aching with tiredness by the time we adjourned at 3 a.m. — and this became increasingly the case, with me feeling rather sidelined as the months went by. I started wondering what I was doing there at all since I had basically drifted in on Mike Harrison’s coat-tails, for although writing and the state of the sf/fantasy field was of vital interest to the Mikes as professional writers it was for me only a sideline, interesting though it might be.

Things were falling apart for me in other ways too. Since moving to London my life had perforce been lived in separate compartments, one for my academic life at UCL which had been quite successful with a paper published in my first year, another for my artistic life with New Worlds and a myriad other strange publications, and a third for my private life. I had once taken a girlfriend round to Mike and Di’s to see if she could be integrated with that part of my life but the experiment hadn’t been a success, and I’d been careful to keep other occasional girlfriends well away from the predatory males of New Worlds, especially from Graham Hall, who regarded any presentable female with a pulse as fair game. But illness brought my faltering academic career to an abrupt end and without my college scholarship I was hard-up, and when the old lady died who had been renting rooms cheaply to various young artistic types like us the house was bought by a property developer who lost no time in evicting us in very brutal ways. With no career, little money and facing homelessness it was clearly time for me to get a proper job, and with Moorcock’s help I was lucky enough to get a publishing job at Longmans in Harlow fairly quickly. The design training at New Worlds and the driving lessons which now got me to Harlow every day had paid off!

But in Notting Hill everything was falling apart. Mike and Di fell out first with Bob, then with me, and a bit later with Moorcock too, then they moved north where they evidently fell out with each other and split up. Charles and his Diane were breaking up. Moorcock and his wife Hilary were divorcing. It was also becoming clear that writing new wave sf was not going to get anyone a mortgage, and some of the writers who had clustered around New Worlds were drifting away or turning to other things. Jimmy Ballard, always a step or two ahead of the game and having had some trouble with his book The Atrocity Exhibition in the USA, eventually turned to more accessible mainstream work with his novel Empire of the Sun which when optioned for a movie by Stephen Spielberg made him rich. When the movie came out it made him even richer.

Brian Aldiss, who had appeared in New Worlds almost from the start and had supported it into its new wave phase by getting it an Arts Council grant, had a best-seller with his autobiographical The Hand-Reared Boy (1970) which spawned two sequels. Tom Disch and his partner Chuck wrote a historical novel about the Carlyles, of all things, which wasn’t so successful. Some of the erstwhile contributors to New Worlds gave up writing altogether. Charles decided to move to New York and without him the business of producing New Worlds as a monthly magazine was going to be well-nigh impossible, so a deal was done by which it would be published by Sphere as a quarterly paperback book, edited initially by Moorcock who asked me to continue as Art Editor. There wasn’t, in all honesty, much art editing to be done but I was pleased to be asked and I did what I could with very limited resources, and now I was frequently calling at Moorcock’s on my own as the sitting room filled with guitars and strange hairy people as Moorcock became involved with the local music scene [touched on in my piece here]. I was glad that I was still involved, and very pleased when Mike (let’s call him that now that the other one has moved offstage) asked me to illustrate some of his novels and to design jackets and covers for some others.  It was fascinating to get glimpses into Mike’s creative processes now and again. On a bookshelf above his desk were a set of handsome books ‘Myth and Legend in Literature and Art’ published by Gresham in the 1920s, and Mike told me that one of them, Hope-Moncrieff’s Romance and Legend of Chivalry, was one he turned to when he was looking for fresh inspiration for his fantasy novels. “When in doubt I turn to good old Hope-Moncrieff,” he said, though it was difficult to know how seriously he meant this. For his more serious novels he made scrapbooks, collecting cuttings, images and memorabilia often picked up in nearby Portobello Road Market, presumably to create a sort of ambience in which to let his imagination rip. I imagine that those scrapbooks will one day be of great interest to scholars as well as being worth a few quid. It was also pleasant to hear the sound of his rather nifty banjo-picking emanating from the toilet downstairs where he liked to practice while I read typescripts and looked at artwork upstairs.

It was fascinating to get glimpses into Mike’s creative processes now and again. On a bookshelf above his desk were a set of handsome books ‘Myth and Legend in Literature and Art’ published by Gresham in the 1920s, and Mike told me that one of them, Hope-Moncrieff’s Romance and Legend of Chivalry, was one he turned to when he was looking for fresh inspiration for his fantasy novels. “When in doubt I turn to good old Hope-Moncrieff,” he said, though it was difficult to know how seriously he meant this. For his more serious novels he made scrapbooks, collecting cuttings, images and memorabilia often picked up in nearby Portobello Road Market, presumably to create a sort of ambience in which to let his imagination rip. I imagine that those scrapbooks will one day be of great interest to scholars as well as being worth a few quid. It was also pleasant to hear the sound of his rather nifty banjo-picking emanating from the toilet downstairs where he liked to practice while I read typescripts and looked at artwork upstairs.

There were movies being made too. Mike’s first Jerry Cornelius novel The Final Programme (originally a serial in New Worlds) was filmed with Jon Finch as Jerry, and it was fascinating to see the character I had drawn so often being brought to life on the screen, then Mike and Jim Cawthorn wrote the script for The Land That Time Forgot based on the novel by Edgar Rice Burroughs, and by way of preparation Jim got books on Hollywood’s classic period from the local library and would regale us with tales of the exploits of David O. Selznick, Irving Thalberg and Harry Cohn, all the more entertaining when related in Jim’s Geordie accent.

New Worlds was ceasing publication as a monthly magazine but there were loyal readers who had taken out subscriptions which could not now be fulfilled, so by way of compensation we produced a special issue just for them, a special ‘Good Taste’ issue, in part a response to the censorship issues that had caused problems for New Worlds when it had serialized Norman Spinrad’s novel Bug Jack Barron causing questions to be asked in Parliament about why the Arts Council was funding an obscene publication. Issue 201 was a thin effort but we knew that it would become a collector’s item and hoped the subscribers would see it that way too. Nobody asked for their money back.

… And so began another phase in the history of New Worlds. We soon found that Sphere’s in-house designers had their own ideas about how New Worlds should look from the outside, and we hoped for the best; in its magazine phase we had been confined to two colours, which Charles had often employed with great ingenuity, but the Sphere covers would be in full colour and might be stunning, though we begged them not to use pictures of space-ships which scarcely represented sf’s new wave, and to begin with they didn’t. Instead they came up with circular images representing god knows what and disappointing everyone, after which it was back to the dreaded space-ships. There were US editions of these books too and their covers were even worse.

After the first four issues Sphere decided to publish New Worlds twice-yearly rather than quarterly, and the editorship was passed on to Charles (who returned from the USA for brief visits) and to Hilary, the former Mrs Moorcock, who also kept me on as the (often notional) Art Editor. As such I got to know Hilary better than I had before and got on with her very well. As well as editing the magazine and looking after the kids — there was a third one now, a late arrival whom they named Max — she liked to get together with her mother occasionally to make and cook a rabbit pie, which they ate for their lunch (“Yum yum,” said Hilary). I always seemed to arrive a bit too late to partake in these treats, though the smell of the delicious rabbit gravy lingered in the flat and amongst the stacks of typescripts. (Mike had remarried and moved to a flat round the corner in Blenheim Crescent so he was still close to the kids.) Hilary was amusing company and a good editor as well as being a fine novelist in her own right (her Polly Put the Kettle On gives her own fictionalized slant on those recent events) and the standard of writing in New Worlds remained high, and although it never sold very many copies, especially in its magazine phase, it was influential, keenly read by a number of young and emerging writers. Neil Gaiman was one, and he has recently had some nice things to say about it here (Mike’s Stormbringer, the first Elric novel, is the second of his The Books That Changed My Life).

Incidentally, although I was involved in endless conversations about the future of sf and fantasy fiction I had little to do with the actual selection of the stories that were published in New Worlds. I was often privileged to read new work as it was being produced by the writers I knew personally, of course, and I naturally read the stories that I was illustrating or getting others to illustrate, but the editorial decisions were made by the Editors with no input from me — except once, when I had done a layout for a story by a certain Bob Franklin called ‘Cinnabar Balloon Tautology’ which I quite liked but which was dropped at the last minute to make way for something else. Putting together the next issue we had a couple of empty pages to fill and I suggested that we use it to fill the hole. “Oh all right, bung it in.” said Charles, and I did. I recently read in the Ansible sf newsletter that Bob Franklin had died and that ‘Cinnabar Balloon Tautology’ had been his only published story.

The arrangement with Sphere ended after three years with their 8th issue (whole number 209), to be taken over by Corgi for a couple of issues in 1975-6 with strange covers that at least weren’t spaceships, and when they pulled out New Worlds might have disappeared altogether but in 1978 Mike acquired a high-quality photocopier and decided to produce a home-made version of the magazine on it: a freebie issue for former subscribers and friends, and once again I was roped in to assist with the design and layouts. The quality improved markedly with the next issue, No. 213 (the ‘Empire’ issue) which contained two cartoon strips by me done in collaboration with Mike and a friend of mine who I’ll call Flip. More about Flip in a moment.

Mike then decided to let others produce their own versions of New Worlds, the next two coming from sympathetic publishing souls in Manchester in the shape of David Britton and Michael Butterworth, who were in the process of setting up their Savoy Books with – I discovered later – Mike and Di in residence. The issues they produced were excellent, addding new dimensions to the New Worlds concept, and Charles returned to London to edit and produce the last of this series, with another great cover from him and some good contents too. This wasn’t meant to be the last issue, however: the next one was entrusted to me and Flip, a school friend who had followed me to London and whom I’d introduced to the New Worlds scene. He’d had various short stories published in the magazine to some acclaim, and a New Worlds done by the two of us was looking promising as a superb story by a young writer named William Gibson had been passed on to us. Flip was in the process of relocating to the North of England and he promptly appointed himself Editor-in-Chief and disappeared northwards with all the material. I did some work on the designs without having anything much to play with, and waited for Flip to deliver his manuscript … and waited, and waited some more. Forty years later, I’m still waiting.

By now I was starting my own publishing company and very preoccupied with that and so the moment passed, and that was effectively the end of New Worlds as a magazine. William Gibson, who had shown enormous patience, eventually withdrew his story; I subsequently learned that it was ‘The Gernsback Continuum’ and when published elsewhere did much to create the genre of Cyberpunk, a wonderful opportunity that we missed thanks to Flip’s shilly-shallying and probably drug-induced lethargy. Thanks a lot, Flip. In this unsatisfactory way my involvement with New Worlds whimpered to its end: it had lasted for ten busy and often fascinating years.

Another ten years went by before New Worlds was eventually revived by David S. Garnett in 1991 as a paperback quarterly published by Gollancz, and it’s subsequently been awakened from its slumbers by others from time to time with no involvement from me. Currently a new version — again as a paperback book — is about to appear from PS Publishing, and from what I gather from the advance information I think I might be rather disappointed as from my perhaps rather biased viewpoint it seems to be looking backwards rather than forwards, with illustrations culled from the early Carnell-era New Worlds and pretty much ignoring the innovations that we were making in the 1960s and 1970s. Obviously I can’t comment on the stories until I’ve read them, though I see a few good writers in the contents-list. To be honest, I’ve been disappointed by all the previous attempts to revive it, feeling that none of the editors (apart from Moorcock himself, who produced a one-off issue to mark its 50th anniversary) have really understood what New Worlds is about, or what it should be. The issues produced by others don’t seem to my possibly jaded eyes to look or feel or, most importantly, read much like the genuine article. Some of us survivors from the magazine’s heyday have been chatting privately and vowing that if New Worlds should ever find itself without a publisher again we would seize back the reins and do it ourselves. We might even do something of the sort anyway, whether we call it New Worlds or something else. There are writers that we always wanted to include in the magazine but were never able to, and some very exciting new ones emerging.

That would be fun. Most of the quarrels of yesteryear have now been largely forgotten, and I would love to re-unite with some of my old colleagues to see if we can recapture some of that first fine frenzy. Please don’t send us any stories or artwork just yet, though. If we decide to go ahead with this scheme it’ll be announced in the usual places and of course I’ll let you know about it here.

-

Graham Hall achieved his ambition, dying from cirrhosis of the liver in 1980 at the age of thirty-three. Michael Moorcock’s Letters from Hollywood (1986) contains an account of this and of the break-up of his marriage to Hilary Bailey who died in 2017 at the age of 80. Her manuscripts and correspondnce are now held at the Bodleian Library. Mike subsequently married Jill Riches, then Linda Steele in 1983 to whom he remains happily hitched. Mike Harrison’s former partner Di (Diane Boardman) and Charles Platt’s Diane (Lambert) have both disappeared from view, untraceable by me. John (‘Ted’) Carnell died in 1972. James Cawthorn and Thomas M. Disch both died in 2008, J.G. Ballard in 2009, Brian Aldiss in 2017 and David Britton in 2020. The other main characters mentioned here are happily still alive.

-

The two available first-hand accounts of life with New Worlds are Charles Platt’s An Accidental Life: volume 2, 1965-1970: the New Worlds Years, which Charles self-published with Amazon (2020), and Michael Moorcock’s fictionalised autobiographical trilogy starting with The Whispering Swarm (2015), and the second volume The Woods of Arcady written and in the pipeline. J.G. Ballard’s autobiography Miracles of Life (2008) has a brief account of his involvement with New Worlds, while Hilary Bailey’s Polly Put the Kettle On (1975) is a novel drawing on her then-recent life.

-

There’s a great deal more about New Worlds in print and online. The Wikipedia entry here provides a useful overview, while Colin Greenland’s The Entropy Exhibiion: Michael Moocock and the British ‘New Wave’ in Science Fiction (1983) gives an academic analysis and David Brittain’s Paolozzi at New Worlds (2013) explores and celebrates the visual aspects. The archive here though seemingly unauthorized has been useful to me as some of the issues featured can be downloaded as PDFs, which has saved me a lot of work. Googling ‘Michael Moorcock’, ‘J.G Ballard’, ‘Charles Platt’ and ‘James Sallis’ (Orthographies 2 never appeared) and ‘M.John Harrison’ will tell you more about the careers of these excellent writers than I can here. Langdon Jones’s anthology The New SF (1969) is a good representative collection from a key period, and there have been many ‘Best of New Worlds’ collections which may be found online sometimes.

-

My apologies to those I haven’t mentioned in this rambling account. I hope to write separate memoirs of John Sladek, Mal Dean and perhaps Mervyn Peake sometime soon, each important to New Worlds in their different ways, and another about Moorcock’s character Jerry Cornelius who loomed large in my artistic life in the time I’ve been writing about.

-

My thanks to Bob Marsden, Charles Platt and Michael Moorcock for good-naturedly allowing me to publish these reminiscences and for gently setting me straight when I got things a bit wrong. The opinions expressed are my own, however, as are any errors that remain.

-

New Worlds has been registered in the USA as a trademark by Michael and Linda Moorcock.

-

Later: Since I posted this piece Langdon Jones has died. He’s mentioned only incidentally in my account but he was an integral member of the New Worlds team while I was involved with it. This isn’t the place for a full obituary or tribute == there’ll be plenty of those — but it’s perhaps worth saying that Lang was largely responsible for the magazine’s high standard of proofreading which he did under the often chaotic conditions that I’ve described. Under his aegis there were hardly any typos. On a personal level he was the kindest fellow, welcoming me into the New Worlds fold and always being complimentary about my artwork. Lang was one of the best of us, now sadly gone.

Very interesting account—thanks for taking the time to write it.

Thank you for this superb and entertaining read about your involment with New Worlds, as a lifelong resident of Tufnell Park myself, your reminiscences hit a sweet spot, I’m now wondering where that bedsit was where all the magic happens,

I hope you publish all these blogs into a nice book and kindle download.

If I remember rightly Mike and Di lived at 46 Anson Road, first floor, the window on the right. Thanks for your comments.

I throughly enjoyed reading your memories of that era of NEW WORLDS. Thanks for writing it, and I very much hope that you’ll also write that account of JERRY CORNELIUS and the various people involved. I never have been quite sure that I’d got it all straight.

Curt Phillips