At my age Christmas is mostly a time for memories and reflection. I’m no longer allowed to smoke or drink so I don’t go to parties or socialize much — in fact because of mobility problems I don’t actually do much at all. It’s ok. I’m still alive, when so many friends and members of my family aren’t. Alive is better.

Antarctica: You can keep your Polar Express and fantasies of Santa Claus living at the North Pole. It’s the southern continent that fascinates me, as it has done ever since I was told as a child that I was related to the great explorer Shackleton. I’ve never managed to work out how this could possibly be true but I don’t care, the spell was cast long ago. I’ve read just about every book on Shackleton and the other early explorers (Scott was a real bungler, wasn’t he?) and Antarctica has become my great imaginary place — no matter that it’s a real place because I shall never be able to go there. It haunts my dreams much more than Atlantis or Middle Earth or Barsoom ever did, and in quiet moments I’m liable to drift away and find myself stranded on the sea-ice or slogging across the Antarctic plateau with Shackleton. Do you remember T.S. Eliot’s question ‘who is the third who walks always beside you?’ in The Waste Land? Well, it’s me.

Antarctica: You can keep your Polar Express and fantasies of Santa Claus living at the North Pole. It’s the southern continent that fascinates me, as it has done ever since I was told as a child that I was related to the great explorer Shackleton. I’ve never managed to work out how this could possibly be true but I don’t care, the spell was cast long ago. I’ve read just about every book on Shackleton and the other early explorers (Scott was a real bungler, wasn’t he?) and Antarctica has become my great imaginary place — no matter that it’s a real place because I shall never be able to go there. It haunts my dreams much more than Atlantis or Middle Earth or Barsoom ever did, and in quiet moments I’m liable to drift away and find myself stranded on the sea-ice or slogging across the Antarctic plateau with Shackleton. Do you remember T.S. Eliot’s question ‘who is the third who walks always beside you?’ in The Waste Land? Well, it’s me.

The Apartment: Feelgood Christmas movies hold little appeal for this old sourpuss. I’ve already explained in an earlier blog piece why I hate It’s a Wonderful Life and while The Apartment (1960) isn’t exactly a Christmas film the action takes place over Christmas and New Year so it qualifies.  I’m a big fan of writer/director Billy Wilder who gave us amongst many other fabulous things Sunset Boulevard and Some Like It Hot, and with Jack Lemmon and Shirley MacLaine on board to interpret Wilder and Diamond’s cynical script how could it fail. One critic wrote “The Apartment dares to show what can happen when someone doesn’t have the opportunity to celebrate Christmas with anyone. And what’s more, there’s no connotation of shame or judgement. It’s matter of fact and fits perfectly within the story. It’s another example of how brilliantly relatable the movie is.” I have it on DVD and may well give it another spin in the days to come.

I’m a big fan of writer/director Billy Wilder who gave us amongst many other fabulous things Sunset Boulevard and Some Like It Hot, and with Jack Lemmon and Shirley MacLaine on board to interpret Wilder and Diamond’s cynical script how could it fail. One critic wrote “The Apartment dares to show what can happen when someone doesn’t have the opportunity to celebrate Christmas with anyone. And what’s more, there’s no connotation of shame or judgement. It’s matter of fact and fits perfectly within the story. It’s another example of how brilliantly relatable the movie is.” I have it on DVD and may well give it another spin in the days to come.

The Beatles: To raise some money for Christmas when I was 16-18 I got temporary jobs as a relief postman in Southport, where the family lived at the time. I did this for three years running. Some of the money did go on Christmas presents, but the main point of it was to have a little trip to London in the gap between Christmas and New Year where I would meet up with my school-friend Chris and where we would have a fine time free of school and parental supervision with some money in our pockets to squander. Chris had a family friend called Evelyn who put us up for free in her house near Finsbury Park — which must have been very near where I live now though I’ve long since lost her address — and London was like a wonderland. To get to the centre we had to go down the tunnels to the tube station — a new experience for me then — and found them swarming with excited kids heading for the Astoria Theatre opposite, where The Beatles were appearing. This was thrilling and it was good to know that they were nearby, but I’d already seen them when they’d played a week in Southport the previous summer, and I was now into jazz. See Marian Montgomery below for more about this. [The Astoria later became The Rainbow, where many fine rock concerts took place [Jimi Hendrix, Bob Marley, Steely Dan, Chuck Berry, Frank Zappa … it was great having it practically on one’s doorstep], but then it was taken over by some religious organization who closed its doors to outsiders.]

bread sauce: Why? Why?

Carol’s diaries: One of this year’s pleasures, albeit a rather bittersweet one, has been reading my late sister’s diaries which came to light after her husband’s death last year. She died in 1993 aged 42 after a long battle with cancer. The two diaries are for 1964 and 1965 when we lived in Southport and she was immersing herself in life at her boarding school just as I was just leaving mine. Over the years we had grown close and I still miss her very much. I won’t publish any extracts from the diaries here as I feel that they should remain private to the family, but reading them has reminded me of many little incidents and told me some things I didn’t know, and I think it’s ok to share a few of them.

Chanel No. 5: My mum was very difficult to buy presents for. This might have been because she basically held the family purse-strings and if she wanted or needed anything for herself that fell within the modest price-range of me and Carol she simply bought it, and if we asked her for suggestions she’d just say “Oh don’t bother about me.” Unhelpful.  The rest of us were only too willing to make our wishes known. Over the years we learned that there were various things that Mum did quite like as gifts — chocolate brazil nuts, for instance, and a small bottle of her favourite scent didn’t go amiss — but the elements of surprise and genuine delight were lacking. We did try. I recall that one Christmas I bought her a set of cake tins in very mod colours, but she just said “Oh, kitchen things” and put them away in a cupboard. In retrospect I can see why kitchen things might not count as proper gifts — but what did? I still don’t know, and now of course it’s much too late.

The rest of us were only too willing to make our wishes known. Over the years we learned that there were various things that Mum did quite like as gifts — chocolate brazil nuts, for instance, and a small bottle of her favourite scent didn’t go amiss — but the elements of surprise and genuine delight were lacking. We did try. I recall that one Christmas I bought her a set of cake tins in very mod colours, but she just said “Oh, kitchen things” and put them away in a cupboard. In retrospect I can see why kitchen things might not count as proper gifts — but what did? I still don’t know, and now of course it’s much too late.

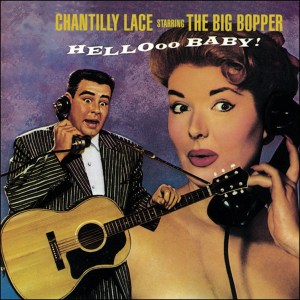

‘Chantilly Lace’: A little surprise in my sister’s diaries has been to learn that when I wasn’t around she and her friends would sneak into my room and listen to records on my souped-up player. Their favourite seems to have been this oldie by the Big Bopper (J.P.Richardson, who had died in the 1959 plane crash that also killed Buddy Holly). If I’d known about the girls’ duplicity at the time I’d have been quite annoyed but now I just smile to myself. Listen to the record here.

‘Chantilly Lace’: A little surprise in my sister’s diaries has been to learn that when I wasn’t around she and her friends would sneak into my room and listen to records on my souped-up player. Their favourite seems to have been this oldie by the Big Bopper (J.P.Richardson, who had died in the 1959 plane crash that also killed Buddy Holly). If I’d known about the girls’ duplicity at the time I’d have been quite annoyed but now I just smile to myself. Listen to the record here.

Chesterton, G.K.: One of the first titles I published when I launched my own firm was The Spirit of Christmas, a selection of Chesterton’s thoughts on the subject. I’d been a fan of Chesterton’s writing for a good many years and built up a sizeable collection of his books, but it was my mother’s idea to make a selection of his writings about Christmas which she thought might make a pleasant little volume that would be a good gift. OK, I said, let’s do it. The resulting book did well, getting good reviews and a rights sale to a US publisher and we wanted to do more Chesterton, but alas Mum developed Alzheimer’s disease and I had to take over as Editor using the royalties from the resulting books to subsidize the cost of the care homes where she had to live for the rest of her life. It was a terribly sad end for such a bright, capable, largely selfless woman, and spending Christmas Day in a care home spoonfeeding dinner to a mother who no longer recognizes you, as I did for seven years, is something that can break your heart.

Christmas pudding: In the first entry in this blog I neglected to mention Shackleton’s Christmas pudding, which was the main reason for including him in the first place. Forgive me. I’m old. I forget things too. Anyway, on his first trip to the Antarctic as a member of Scott’s Discovery expedition in 1902 Shackleton was chosen to accompany Scott and Wilson in their attempt to cross the Ross ice shelf and go further south than anyone had gone before.

It was a gruelling journey but on Christmas day, when things were getting really tough with the men showing signs of frostbite and scurvy, Shackleton surprised his tent-mates by producing a Christmas pudding that he had hidden: “The other two chaps did not know about the pudding,” he wrote later. “It only weighed six oz. And I had stowed it away in my socks (clean ones) in my sleeping bag, with a little piece of holly. It was a glorious surprise to them, that plum pudding, when I produced it.”

Charles Dickens: Said to have invented the modern Christmas in A Christmas Carol (1843). If you find a copy of the first edition in your Christmas stocking you’ll be able to spend your next few Chistmasses sunning yourself in the Bahamas, and to hell with snow and plum puddings.

dwarves: Through books, movies, tv, circuses and pantomimes dwarves (or should it be dwarfs?) are inextricably linked with Christmas, with roots going back to ancient mythology. In modern times Walt Disney had much to do with popularizing this with his animated movie Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937) and in the same year The Hobbit by J.R.R.Tolkien was published. Two more differing notions of dwarves could scarcely be imagined,

and while Snow White remains popular no-one could have predicted how Tolkien’s vision would come to influence and eventually dominate the field of Fantasy. I once set myself the task of listing the names of all the famous dwarves in fiction — I was stuck in a very boring job — starting with Tolkien, who named dozens of them. This was in the late 1970s when post-Tolkien fantasy fiction was becoming enormously popular, much of it in the vein of what became known as ‘Sword and Sorcery’ featuring a hero with a big sword, magical powers and, very often, a dwarfish sidekick, but cataloguing their names soon became an impossible, never-ending task. I liked some of these dwarves — Moonglum (a creation of Michael Moorcock) and the Gray Mouser (from Fritz Leiber) were two favourites — but the whole thing soon became very formulaic and I wasn’t too sorry to abandon it.

Emanations: 2023 has seen more of my work in print thanks to Carter Kaplan, who had published my piece about my involvement with the magazine New Worlds in the previous issue of Emanations. Encouraged, I did some computer graphics and submitted a dozen of them to Carter thinking that he might use a couple of them, but to my surprise he has published all of them as a portfolio. Very flattering.

four-engined bomber: Dad was useless at keeping a secret. As a boy I was very keen on assembling plastic model kits, mostly the ones made by Airfix, and on many Saturday mornings my friend Michael and I would catch the bus that took us to the model shop in the centre of Leeds and each buy another kit to add to our collection of planes, vintage cars and even galleons (doing the rigging was tricky), so it was easy to buy a present for me. Another kit would be just fine. As Christmas 1957 approached Dad started casually mentioning a four-engined bomber which might or might not be coming my way (“Behave yourself or you won’t get that four-engined bomber.”), which was puzzling as we were very familiar with the Airfix range and none of their basic kits seemed to fit this description.

Well, Dad had surpassed himself with the newest, biggest and best kit to be had anywhere, a Boeing B-29 Superfortress which was indeed a bomber with four engines, and when Michael, whose family was much better off then we were, came round on Christmas morning proudly bearing his identical Superfortress kit to show me he was nice enough to reveal hardly a trace of disappointment to find that I’d got one too.

game chips: When I was young and inexperienced in the ways of the world I found myself ordering a meal in a hunting-lodge type of restaurant — can’t remember where it was or why on earth I was in such a place, but seeing ‘game chips’ on the menu I thought they sounded good and ordered them along with the steak, chops or whatever it was I was having.  A treat in store, I thought, but what a disappointment they turned out to be: just a handful of perfectly ordinary potato crisps of the sort sold by Messrs Walker or Golden Wonder, and only five or six of them at that. You might think I’d learned my lesson but no, only last Christmas as I got over my bout of hypothermia (see below) I was hungry and decided to order a meal from a nearby gastro-pub: a gammon steak with various sides and you guessed it. They couldn’t still be dishing up crisps as game chips in these places could they, but they were. Restaurateurs! If you advertise game chips you must make them yourself on the premises. Potato crisps won’t do.

A treat in store, I thought, but what a disappointment they turned out to be: just a handful of perfectly ordinary potato crisps of the sort sold by Messrs Walker or Golden Wonder, and only five or six of them at that. You might think I’d learned my lesson but no, only last Christmas as I got over my bout of hypothermia (see below) I was hungry and decided to order a meal from a nearby gastro-pub: a gammon steak with various sides and you guessed it. They couldn’t still be dishing up crisps as game chips in these places could they, but they were. Restaurateurs! If you advertise game chips you must make them yourself on the premises. Potato crisps won’t do.

Gilbert & Sullivan: My dad was very fond of music, especially the lighter sorts of classical music: Mozart and Rossini, for instance, but not much Beethoven and definitely no Wagner. He was a great fan of Gilbert & Sullivan and aimed to get every one of their works on record.  There are more of them than you might think and it often fell to me as a keen record buyer on my own account to find some of G&S’s more obscure works for him as Christmas or birthday presents, e.g. Ruddigore and Princess Ida, which I dutifully did for many years. When he died his collection passed to me, and I haven’t yet had the heart to get rid of them. I’ve just bought a new record player, however, so maybe I’ll give some of them one last spin before they go to the charity shop. I’ve had a soft spot for The Mikado since Dad took me to see a D’Oyly Carte production of it in Leeds when I was small, so that might be the one I’ll play first.

There are more of them than you might think and it often fell to me as a keen record buyer on my own account to find some of G&S’s more obscure works for him as Christmas or birthday presents, e.g. Ruddigore and Princess Ida, which I dutifully did for many years. When he died his collection passed to me, and I haven’t yet had the heart to get rid of them. I’ve just bought a new record player, however, so maybe I’ll give some of them one last spin before they go to the charity shop. I’ve had a soft spot for The Mikado since Dad took me to see a D’Oyly Carte production of it in Leeds when I was small, so that might be the one I’ll play first.

hypothermia: I got things badly wrong last Christmas. I’d been in London for several months and at the last minute I decided to drive down to Broadstone for the holiday, assuming that the house there would be pretty much the same as I’d left it. It wasn’t. Powered through a prepayment meter, because of standing charges being repeatedly deducted the credit had run out, the electricity had been cut off and the place was freezing cold and damp. Being Christmas the shops with paypoints where the meter could be topped up were closed and the neighbours were away, so I had to cope as best I could in the cold and dark. I found a couple of candles, set them up them next to my chair — the bed upstairs was dank — and settled down to try and sleep, but as the cold bit I couldn’t get off and I just tried to get some warmth from the candles.  This didn’t work and I think that night was the longest and worst of my life, daylight brought little relief, and the next night was no better. In retrospect I can see that there are things that I might have done: I could have got back into the car and run the engine all night, or driven away to try and find a hotel room, but I now know that intense cold affects the judgement and saps the will, and I just sat and suffered, getting colder and colder. I began to see why Captain Scott, stranded in his tent in a blizzard without food or fuel only a dozen miles from safety, just gave up and died. And hypothermia, when the cold gets into your bones, hurts. It continued to hurt for a while longer when the shops opened up again and I was able to start heating the house, which took several days. As I write this on Christmas Eve 2023 I’ve made sure that the electricity meter is well topped up.

This didn’t work and I think that night was the longest and worst of my life, daylight brought little relief, and the next night was no better. In retrospect I can see that there are things that I might have done: I could have got back into the car and run the engine all night, or driven away to try and find a hotel room, but I now know that intense cold affects the judgement and saps the will, and I just sat and suffered, getting colder and colder. I began to see why Captain Scott, stranded in his tent in a blizzard without food or fuel only a dozen miles from safety, just gave up and died. And hypothermia, when the cold gets into your bones, hurts. It continued to hurt for a while longer when the shops opened up again and I was able to start heating the house, which took several days. As I write this on Christmas Eve 2023 I’ve made sure that the electricity meter is well topped up.

ice skating: The best Christmas holiday when I was a teenager was during the winter of 1962-3, known as The Big Freeze, which was one of the coldest periods on record in the United Kingdom. Our house in Bromborough (on the Wirral Peninsula) was heated by a roaring coal fire in the back parlour, and if the bedrooms remained unheated and ice formed on the inside of the windows overnight that didn’t seem to matter much in those days. We huddled. The news on tv showed snowy scenes all over the country with people snowed in and vehicles abandoned, and when a letter arrived from my school saying that the start of term would have to be delayed because supplies couldn’t get through I was overjoyed. I and my friend Brian decided to check out Raby Mere, a favourite haunt of ours, to see if it had frozen over, and we found a magical scene awaiting us.

The Mere was usually more or less deserted but this morning it was crowded with skaters and sliders and kids having snowball fights, and many more had wrapped themselves up warm and turned out to watch the fun. Where on earth had they come from, all these people with ice skates just waiting for weather like this? Although I’d been a keen roller-skater when I was a bit younger I’d never ice-skated so Brian and I contented ourselves with joining in the creation of a huge slide which stretched right across the Mere. I haven’t been able to find a photo of this but, believe me, it really was like a scene from a Christmas card. Eventually the thaw came, of course, and I had to go back to school, boo chizz.

Ilford Sportsman: My parents were pretty generous present-givers. When I wanted a racing bike they got me one. A duffel coat to keep me warm in the winter? No problem. And when I asked for a decent camera they got me an Ilford Sportsman, leather case included,  and photography became a major hobby of mine for some years to come. The one thing I wanted and didn’t get was an encyclopædia. Year after year when Christmas or my birthday came around I’d ask for an encyclopædia and couldn’t really understand why I didn’t get one. I was considered a bright kid and surely it would have been beneficial. Did they want me to remain ignorant of some things, e.g. detailed human anatomy and the Facts of Life? I’m still a bit puzzled by this. Anyway, there was no encyclopædia for Richard and that, in a nutshell, is why he remains unmarried and will never win Pointless.

and photography became a major hobby of mine for some years to come. The one thing I wanted and didn’t get was an encyclopædia. Year after year when Christmas or my birthday came around I’d ask for an encyclopædia and couldn’t really understand why I didn’t get one. I was considered a bright kid and surely it would have been beneficial. Did they want me to remain ignorant of some things, e.g. detailed human anatomy and the Facts of Life? I’m still a bit puzzled by this. Anyway, there was no encyclopædia for Richard and that, in a nutshell, is why he remains unmarried and will never win Pointless.

Karl Jenkins – Stella Natale: Makes a pleasant change from Sleigh Ride and the usual run of endlessly recycled Christmas hits. Give this a listen here. It’s good.

Jukel: A border collie, one of three belonging to my university friends Bernard and Kathy with whom I used to spend the Christmas/New Year holiday each year as soon as we could escape our respective families. (Christmas can be a magical time when children are involved, but spending the holiday with your parents when you’re grown up is a different matter.) I suppose I shouldn’t have had a favourite among the dogs, but Jukel was mine.  The name is apparently the gypsy term for a dog. She bullied the two other (male) dogs constantly, to our great amusement, but she could also be very affectionate. This arrangement continued for many years, but Bernard and Kathy and all the dogs are dead now. So it goes.

The name is apparently the gypsy term for a dog. She bullied the two other (male) dogs constantly, to our great amusement, but she could also be very affectionate. This arrangement continued for many years, but Bernard and Kathy and all the dogs are dead now. So it goes.

The Kinks – ‘Father Christmas’: I liked the Kinks right from ‘You Really Got Me’ in 1964 and when I eventually moved to London was delighted to find that they were in effect our local group in nearby Hornsey and Muswell Hill. Still are. ‘Father Christmas, give us the money’ was a sentiment dear to our young hearts, ungrateful wretches that we were. I thought I was being grown-up and sophisticated by also liking ‘Santa Baby’ by slinky Eartha Kitt.

Llandudno: We evidently had a family holiday there at Christmas in 1961, though I have no memory of it. The camera doesn’t lie, however, and the one photo surviving from this jollity shows my sister Carol competing in some sort of fancy-dress contest decked out as goodness knows what. A note on the back of the photo says that she came 2nd.

Bodlondeb Castle, incidentally, was a Methodist holiday hotel, one of a string of such establishments where we Joneses spent most of our holidays when Carol and I were young. There were a lot of communal activities in these places: outings, concerts, sports and games as well as group worship and, for the young folk, midnight feasts and budding romances. My parents first met each other at one such place in the 1930s and continued to patronize them right to the end, when cheap package holidays abroad changed people’s holiday-going habits and most of them were closed down and sold off, more’s the pity as they were wonderful if you didn’t mind the absence of booze. It wasn’t long before I too was looking for more exciting kinds of holidays, however:

Marian Montgomery: So my pal Chris and I are schoolboys at large in London and having quite a merry time [see Beatles above]. We have smoked cigarettes openly and got served drinks in pubs without getting arrested or thrown out, we have been to the theatre (Son of Oblomov with Spike Milligan, mind-blowing), the cinema (The Longest Day, a mistake, very boring) and a strip club, and now as budding jazz fans we want to see if we can get into Ronnie Scott’s.

It’s just getting dark and the proprietor is standing at the door of his club exactly as he is in the photo. Chris and I approach him nervously, trying to look as old and mature as we can, and ask him how much it is to get in. “How much have you got?” says Ronnie. We pretend to scrabble about in our pockets and say that we can raise about two bob each. “Well, you’re in luck,” says Ronnie, “Because tonight admission is just two bob.” — a ridiculously cheap fee — and amazingly he ushers us in, but says we’ll have to sit in a dark corner. Licensing laws? I don’t know, but we’re very happy to be inside, and we haven’t been there long before I feel a hand clutching mine, a soft evidently female hand, and a soft female voice says “For god’s sake take me to the bandstand. I can’t see a damn thing.” I manage to lead her there without bumping into anything or tripping over, and as the lights go up I see that this is Miss Montgomery, the glamorous American jazz singer and the star of the show. She thanks me and I feel like a very cool dude indeed.

needle drop: Mum’s birthday fell on 5th January — Twelfth Night, when Christmas decorations are traditionally taken down, so we waited until then before taking ours down, by which time the tree was shedding its needles all over the carpet and some serious vacuuming had to be done. By Mum, of course. For another kind of needle drop see under vinyl.

oratorio: Yorkshire is a very musical county, and as Christmas approaches rehearsals are taking place in churches, village halls and theatres all over the county as amateur choirs are preparing to present Handel’s Messiah yet again, though some of them hire a professional singer or two to help things along — and why not? It’s a fine, stirring piece which I’ve heard many times in such places.

pea and pie supper:  The regular conclusion of many social gatherings in my youth, as advertised in the Notices, the announcements of what would be happening in the church in the forthcoming week, e.g. “And on Wednesday at 8 o’clock the Men’s Prayer Meeting will be held in Room 3b, and this will be followed by a pea and pie supper.” My sister and I could reduce ourselves to giggles by saying “pea and pie supper” in a broad Yorkshire accent just too quietly for Dad to hear, but when we’re old enough to partake in such things ourselves, we don’t. The times they are a-changing. Visiting the parents at Christmas as an adult, however, I and Dad sometimes fancy a pea and pie supper as a sort of guilty pleasure, and there’s an excellent pie shop just around the corner …

The regular conclusion of many social gatherings in my youth, as advertised in the Notices, the announcements of what would be happening in the church in the forthcoming week, e.g. “And on Wednesday at 8 o’clock the Men’s Prayer Meeting will be held in Room 3b, and this will be followed by a pea and pie supper.” My sister and I could reduce ourselves to giggles by saying “pea and pie supper” in a broad Yorkshire accent just too quietly for Dad to hear, but when we’re old enough to partake in such things ourselves, we don’t. The times they are a-changing. Visiting the parents at Christmas as an adult, however, I and Dad sometimes fancy a pea and pie supper as a sort of guilty pleasure, and there’s an excellent pie shop just around the corner …

pigs in blankets: “UK faces Christmas without pigs in blankets amid labor shortage” — alarming newspaper headline published as I write this. Let’s hope this is resolved before the big day coz I love them and left to my own devices will cook them at any opportunity, Christmas or not, and if there are any left over after the main meal is eaten I’ve found that they are excellent in sandwiches: three or four of them between two slices of crusty white bread. I’m thinking of calling these ‘pigs in blankets in a warm cosy bed’. Sausages also loomed large in my sister’s diaries. She recorded details of practically every meal she ate and often at school and sometimes at home too it was sausages. She says that on one occasion I cooked sausage and chips for her and her friends which like so much else has gone from my memory, but it’s plausible because these were among the very few things that I could cook at that age (the others were cheese on toast and toast without cheese). I’m also very partial to cheese straws at Christmastime but I didn’t learn how to make them until many years later, relying in the meantime on Mum to provide the treats, as usual.

Sausages also loomed large in my sister’s diaries. She recorded details of practically every meal she ate and often at school and sometimes at home too it was sausages. She says that on one occasion I cooked sausage and chips for her and her friends which like so much else has gone from my memory, but it’s plausible because these were among the very few things that I could cook at that age (the others were cheese on toast and toast without cheese). I’m also very partial to cheese straws at Christmastime but I didn’t learn how to make them until many years later, relying in the meantime on Mum to provide the treats, as usual.

quail eggs:  I’ve only ever eaten these festive delicacies once, when they were served as an hors d’oeuvre at a rather posh wedding I attended. Quite tasty though very small. No ill effects.

I’ve only ever eaten these festive delicacies once, when they were served as an hors d’oeuvre at a rather posh wedding I attended. Quite tasty though very small. No ill effects.

Rupert annuals: When I was a lad in Yorkshire each Christmas brought the latest Rupert Bear annual from my grandparents in Harrogate, and when I was deemed to have outgrown Rupert the annuals were sent to my younger sister. We both loved Rupert, and I can still read his adventures with pleasure though they’re getting hard to find these days.

It wasn’t just Rupert himself that appealed. He had many friends who regularly appeared in the stories, among them

• Bill Badger

• Algy Pug

• Podgy Pig

• Edward Trunk, an elephant

• Ping Pong, magical, female Pekingese

• Freddy and Ferdy Fox, mischievous twins

• Bingo the brainy pup

• Gregory Guinea Pig

• Constable Growler

• ‘Rastus Mouse

• Tigerlily, daughter of the Chinese conjurer

• The Professor, who lived in a tower

Most of them lived in or around Nutwood, a pretty village somewhere in England, and I liked the idea that most of Rupert’s adventures took place in the surrounding woods and meadows, though he sometimes went further afield: to the South Seas, for instance, but he still got home in time for tea. I think that Nutwood was the first of the great imaginary places of my dreams.

selection box: As far back as I can remember each member of the family got one of these from Santa Jones (Dad) in their Christmas stocking, and this continued until we were well into adulthood — until his death at the age of 83, in fact. I don’t have much of a sweet tooth but each year I somehow managed to devour the entire contents of my box over the holiday period all by myself.

snowball: A drink made by mixing Advocaat, a sort of commercially-produced egg nog, with lemonade. Dad discovered it one Christmas late in life after decades of teetotalism, and developed a taste for it. By this time he was in a lot of pain and becoming quite difficult; a snowball cheered him up and helped things along, so we didn’t discourage him.

turkey: Dad wouldn’t eat it, or any other form of poultry. It wasn’t that he was allergic to it. He could eat it when he absolutely had to, e.g. at a wedding or funeral where he was presiding and it would have been very rude not to (have I mentioned that he was a clergyman?). He simply hated it. This made things awkward for Mum at Christmas as there was no way she would let the rest of the family go without a proper turkey dinner with all the trimmings (as they say), so she cooked two dinners: steak for Dad and turkey etc. for the rest of us. She juggled things very well and pretty cheerfully in the circumstances, I must say.

The only raffle that I’ve ever won had a turkey as the prize — a live one, available for collection from a nearby farm on Christmas Eve … I’ll save the story of that fiasco for another time.

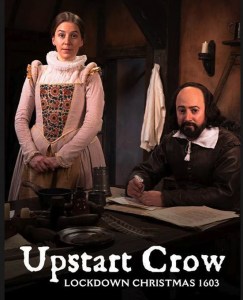

Upstart Crow: This year my Christmas present to myself — or one of them, since I have to look after myself these days — is the boxed set of this Shakesperian tv comedy series starring David Mitchell with a fine supporting cast, notably Gemma Whelan as Kate, and including all the Christmas specials. Their two-hander made under the constraints of lockdown was brilliant. Script by Ben Elton.

vinyl: People keep telling me that it’s making a comeback, but for some of of us it’s never been away. We don’t mind the slight hissing sound made when the needle drops and engages with the groove on the record, in fact we rather like it and miss it when playing CDs or listening to Spotify or whatever.

worst Christmas present ever: And the wooden spoon goes to … a set of three wooden spoons in fact, which I actually received one year from a family member, a notorious skinflint. They were very poor spoons too, looking as though they’d been crudely carved from bits of an old orange box with a blunt penknife, and I knew that he’d bought them from the local market, price 50p. On the plus side, all these years later I still use a couple of them for stirring purposes when I make soup.

Xbox: I don’t go in for any form of gaming so have no need for this or other such devicea, which I’m told are popular with some people at Christmas. I don’t feel I’m missing out on anything, and it saves me quite a few quid. X is also the new name for what used to be called Twitter and I’ve never been interested in that either.

Yeats, W.B.: ‘The Second Coming’

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Surely some revelation is at hand;

Surely the Second Coming is at hand.

The Second Coming! Hardly are those words out

When a vast image out of Spiritus Mundi

Troubles my sight: somewhere in sands of the desert

A shape with lion body and the head of a man,

A gaze blank and pitiless as the sun,

Is moving its slow thighs, while all about it

Reel shadows of the indignant desert birds.

The darkness drops again; but now I know

That twenty centuries of stony sleep

Were vexed to nightmare by a rocking cradle,

And what rough beast, its hour come round at last,

Slouches towards Bethlehem to be born?

Written in 1919, seems more pertinent than ever at the end of 2023 doesn’t it.

Yule log? Nah.

Zimtsterne: Traditional German star-shaped Christmas cookies flavored with cinnamon. As one authority puts it, “The holidays simply aren’t the same without Zimtsterne!” Here’s a recipe.

Here’s a recipe.

Happy munching!

comedian and game-show host isn’t perhaps an obvious place to find oneself wrong-footed by obscure words and phrases but Bob Monkhouse’s contains a bunch which had me scurrying to the dictionary. Here in no particular order are some of them, to which I’ve appended definitions for any readers who may be as ignorant as I recently was:

comedian and game-show host isn’t perhaps an obvious place to find oneself wrong-footed by obscure words and phrases but Bob Monkhouse’s contains a bunch which had me scurrying to the dictionary. Here in no particular order are some of them, to which I’ve appended definitions for any readers who may be as ignorant as I recently was:

Pretty soon these same boys were yelling “Banzai!” as they attacked each other (and me) with pillows after lights out. There were some nasty books circulating too dealing in rather too much detail with Japanese war atrocities, such as The Camp on Blood Island and The Knights of Bushido. These things revolted me but they were inescapable, yet as the years went by and as the dust of Nagasaki and Hiroshima settled our perception of the Japanese slowly changed, and by the 1980s my company was trading with Japanese publishers very happily and for some years now I’ve been driving Japanese cars, but though It’s probably unworthy of me I can’t help wondering where all the cruelty went. In peacetime did it just melt away, never to be seen or mentioned again? Perhaps I’m wrong even to mention it here.

Pretty soon these same boys were yelling “Banzai!” as they attacked each other (and me) with pillows after lights out. There were some nasty books circulating too dealing in rather too much detail with Japanese war atrocities, such as The Camp on Blood Island and The Knights of Bushido. These things revolted me but they were inescapable, yet as the years went by and as the dust of Nagasaki and Hiroshima settled our perception of the Japanese slowly changed, and by the 1980s my company was trading with Japanese publishers very happily and for some years now I’ve been driving Japanese cars, but though It’s probably unworthy of me I can’t help wondering where all the cruelty went. In peacetime did it just melt away, never to be seen or mentioned again? Perhaps I’m wrong even to mention it here.

The high-pitched voice turned out to belong to the drummer, a hairy fellow who also wrote it. It took me 35 years to identify the thing, and then I did so only by accident. Anyway, I downloaded the track and now play it two or three times day in the hope of getting sick of it and banishing the earworm forever, but at the moment I still like it.

The high-pitched voice turned out to belong to the drummer, a hairy fellow who also wrote it. It took me 35 years to identify the thing, and then I did so only by accident. Anyway, I downloaded the track and now play it two or three times day in the hope of getting sick of it and banishing the earworm forever, but at the moment I still like it. On the left is my Nana who I claim as the original Betty of Bettys Café fame — she was never very keen on smiling for the camera — then my mother, then my grandfather J.J. who ran Bettys for many years but died young, and finally Uncle Ray. It doesn’t do to dwell too much in the past, however, and I’m glad to say that my family in New Zealand are keeping me plentifully supplied with photos of the new generation:

On the left is my Nana who I claim as the original Betty of Bettys Café fame — she was never very keen on smiling for the camera — then my mother, then my grandfather J.J. who ran Bettys for many years but died young, and finally Uncle Ray. It doesn’t do to dwell too much in the past, however, and I’m glad to say that my family in New Zealand are keeping me plentifully supplied with photos of the new generation: That’s Mia at the back, then (from the left) Isabelle, Finn and Madeleyne: one great-nephew and three great-nieces. Can these beautiful kids really be related to ugly old me?

That’s Mia at the back, then (from the left) Isabelle, Finn and Madeleyne: one great-nephew and three great-nieces. Can these beautiful kids really be related to ugly old me?

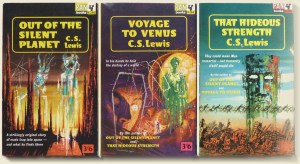

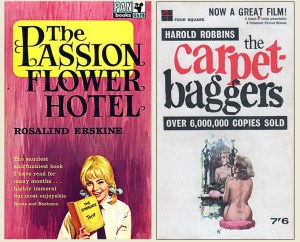

I belong to various online groups devoted to the celebration of vintage paperbacks, of which I possess hundreds, where members upload pictures of the books in their collections and of their latest finds. Most of these books are from the genres of thrillers and science fiction with splendidly lurid covers, and occasionally one of these brings back sharp memories, e.g. The Passion Flower Hotel which was considered a very naughty book in the early 1960s. It was read avidly by my sister Carol and the other girls at her boarding school where it had to be hidden from the teachers and, at home, from parents too. Tee hee. I wasn’t averse to a bit of sleaze myself and remember a few books that I read at the time in search of cheap thrills. One was The Ginger Man by J.P. Donleavy, which I enjoyed and actually admired as a novel, but sleazier by far was The Carpetbaggers. Does anyone read Harold Robbins these days? I doubt it.

I belong to various online groups devoted to the celebration of vintage paperbacks, of which I possess hundreds, where members upload pictures of the books in their collections and of their latest finds. Most of these books are from the genres of thrillers and science fiction with splendidly lurid covers, and occasionally one of these brings back sharp memories, e.g. The Passion Flower Hotel which was considered a very naughty book in the early 1960s. It was read avidly by my sister Carol and the other girls at her boarding school where it had to be hidden from the teachers and, at home, from parents too. Tee hee. I wasn’t averse to a bit of sleaze myself and remember a few books that I read at the time in search of cheap thrills. One was The Ginger Man by J.P. Donleavy, which I enjoyed and actually admired as a novel, but sleazier by far was The Carpetbaggers. Does anyone read Harold Robbins these days? I doubt it. I knew that they would be a con, and that they wouldn’t really enable me to see through women’s clothes to their naked bodies — something I was very keen to see when I was 13 or so — and when I finally got hold of a pair (of x-ray specs, not yet naked women) by a most circuitous route of course they didn’t.

I knew that they would be a con, and that they wouldn’t really enable me to see through women’s clothes to their naked bodies — something I was very keen to see when I was 13 or so — and when I finally got hold of a pair (of x-ray specs, not yet naked women) by a most circuitous route of course they didn’t. On the other side of the moat is Badfort, occupied by a crowd of ne’er-do-wells led by Beaver Hateman, and they are Uncle’s enemies. They dress in ragged sacking, get drunk on Black Tom and Leper Gin, and they constantly plot and scheme to embarrass and bring down the Dictator of Homeward. Rev. Martin had an incredible, teeming, hilarious imagination, and if I’d worried that there might be some sort of moral attached to all this I needn’t have. It was pure nonsensical bliss.

On the other side of the moat is Badfort, occupied by a crowd of ne’er-do-wells led by Beaver Hateman, and they are Uncle’s enemies. They dress in ragged sacking, get drunk on Black Tom and Leper Gin, and they constantly plot and scheme to embarrass and bring down the Dictator of Homeward. Rev. Martin had an incredible, teeming, hilarious imagination, and if I’d worried that there might be some sort of moral attached to all this I needn’t have. It was pure nonsensical bliss. Going through some old papers I found various letters and cards from my father which he had signed “from the Aged Parent” or just “Aged P.” Dickensians will of course recognize this soubriquet from Great Expectations which as a family we knew from the TV version, one of the classic serials that the BBC showed at Sunday teatimes in the 1960s. The scene in question occurs when Mr Wemmick is showing Pip round the odd little wooden house that he has built for himself and his father in the manner of a tiny castle complete with battlements, a flagpole, a minuscule moat with a drawbridge, and a small cannon on the roof which is fired every night at nine o’clock to please the otherwise deaf old man, whom Wemmick refers to as the Aged Parent. This greatly amused my father who promptly adopted the title for himself, even though he was then only in his fifties — considerably younger than I am now, I realize with some shock.

Going through some old papers I found various letters and cards from my father which he had signed “from the Aged Parent” or just “Aged P.” Dickensians will of course recognize this soubriquet from Great Expectations which as a family we knew from the TV version, one of the classic serials that the BBC showed at Sunday teatimes in the 1960s. The scene in question occurs when Mr Wemmick is showing Pip round the odd little wooden house that he has built for himself and his father in the manner of a tiny castle complete with battlements, a flagpole, a minuscule moat with a drawbridge, and a small cannon on the roof which is fired every night at nine o’clock to please the otherwise deaf old man, whom Wemmick refers to as the Aged Parent. This greatly amused my father who promptly adopted the title for himself, even though he was then only in his fifties — considerably younger than I am now, I realize with some shock.

Those wonderfully crazy, extreme action and kung-fu movies were so much a product of exuberance in a city that was enjoying wild growth as a function of minimally controlled capitalism. We’re not going to see anything like that under CCP control.

Those wonderfully crazy, extreme action and kung-fu movies were so much a product of exuberance in a city that was enjoying wild growth as a function of minimally controlled capitalism. We’re not going to see anything like that under CCP control.